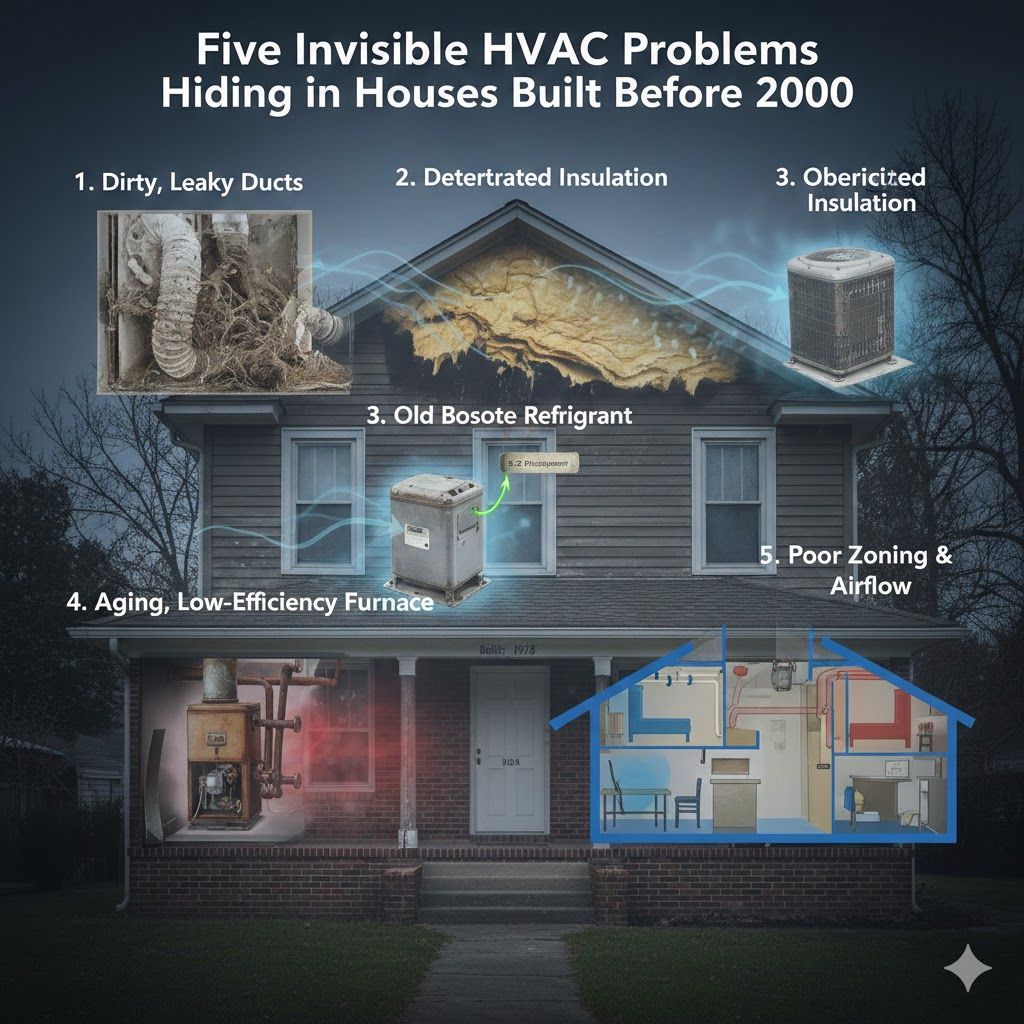

5 Invisible HVAC Problems Hiding in Houses Built Before 2000

5 invisible HVAC problems lurk in many homes built before 2000, quietly wasting energy, reducing comfort, and hurting air quality long before a system actually “breaks.” Addressing them proactively often costs less than waiting for a major failure.

1. Leaky, Aging Ductwork Behind the Walls

In homes built before 2000, ductwork is often original to the house and has been expanding, contracting, and flexing for decades. Over time, joints loosen, tape dries out, and small gaps form at elbows and seams that most homeowners never see.

Those small gaps have big consequences.

Conditioned air escapes into attics, crawlspaces, or wall cavities instead of reaching the rooms you’re trying to cool or heat.

Your system has to run longer to hit the same thermostat setting, driving up energy bills and wear on equipment.

Because the leaks are hidden, the symptoms can be confusing: one room never gets comfortable, the thermostat “seems wrong,” or the system runs constantly on extreme weather days. Many homeowners assume the equipment is too small, when the real issue is air lost in the duct system.

What to do:

Have a professional inspect accessible duct runs, connections at the air handler, and any visible trunk lines for loose joints, disconnected sections, and failed tape or mastic.

Ask about duct leakage testing; in many older homes, sealing and minor redesign of the duct system can improve comfort more than upgrading the equipment alone.

2. Outdated or Improperly Designed Duct Layout

Even if ducts are not severely leaky, the design itself is often the hidden problem in pre‑2000 homes. Older design standards didn’t account for today’s efficiency expectations, added rooms, or the way people actually live in open floor plans.

Common design issues include:

Undersized return air pathways, making the system “strangle” for air and causing noisy vents and uneven temperatures.

Long duct runs with too many bends, which create resistance and starve distant rooms of airflow.

Single central return for an entire home, leaving bedrooms and additions with poor circulation when doors are closed.

These design flaws don’t show up as an error code or an obvious “broken” part; they show up as chronic hot and cold spots, stuffy rooms, and a system that seems to work hard without delivering comfort.

What to do:

Have airflow measured at supply registers and returns to identify rooms that are under‑served.

Discuss options like adding additional returns, resizing key ducts, or installing dampers and zoning to balance airflow to problem areas.

3. Hidden Airflow Restrictions and Blockages

Older homes accumulate “friction” in the system that slowly chokes airflow, but those restrictions are rarely obvious at a glance. Homeowners may change filters regularly yet still have poor airflow because of issues no one sees without opening the system.

Common invisible restrictions include:

Dust and debris buildup inside ductwork over decades, especially in return ducts where unfiltered air enters.

Partially closed or blocked dampers, either left shut after past work or jammed in place.

Evaporator coils clogged with lint, dust, and biological growth that reduce the system’s ability to move air and remove heat.

These issues can cause:

Noisy vents and whistling sounds as air struggles to move.

Longer run times because the system can’t move enough air over the coil.

Increased risk of freezing coils or overheating components.

What to do:

Schedule a professional inspection that includes static pressure measurements and a close look at the indoor coil and accessible ductwork.

Where appropriate, consider professional duct cleaning and sealing, especially in homes that have seen renovations, pets, or smoking indoors over many years.

4. Poor Indoor Air Quality from “Invisible” Contaminants

Indoor air quality in homes built before 2000 often suffers from a combination of older construction, gaps in the building shell, and aging HVAC components. The air may look clear, but contaminants circulate through the system with every cycle.

Factors that quietly undermine indoor air quality include:

Dust, pollen, and outdoor pollutants entering through older windows, doors, and attic penetrations, overwhelming the system’s filter.

Years of dust and microbial buildup inside ducts that re‑circulate with each heating or cooling cycle.

Older systems not designed for high‑efficiency filtration, making it difficult to capture fine particles without stressing the blower motor.

Homeowners may notice more allergy symptoms, dry eyes, or musty odors, but not connect them to the HVAC system. In some cases, duct condensation and leakage can even support mold growth inside walls or ceilings, especially in humid climates.

What to do:

Use properly sized, quality filters that the existing blower can handle, and change them on a consistent schedule.

Ask about indoor air quality upgrades such as better filtration options, UV lights, or dehumidification, particularly in climates where humidity is a major factor.

Have ducts inspected for signs of moisture, staining, or microbial growth, and address leaks or condensation sources promptly.

5. Outdated Controls and Thermostat Strategy

The thermostat and control strategy in many pre‑2000 homes lag far behind what modern systems can do for comfort and efficiency. Yet because the thermostat “still works,” many homeowners don’t see it as a problem.

Issues with older controls include:

Manual, non‑programmable thermostats that can’t automatically adjust temperatures when you’re asleep or away.

Inaccurate temperature sensing, causing the system to overshoot or undershoot the desired temperature.

Single‑zone control for an entire house, even when the layout would benefit from separate zones for upstairs/downstairs or additions.

The result is comfort complaints and higher energy use, even if the equipment itself is in decent condition. In older homes, this can be especially noticeable in rooms far from the thermostat or with large windows and solar gain.

What to do:

Upgrade to a modern programmable or smart thermostat compatible with your existing system, and use scheduling features to match your daily routine.

In multi‑story or spread‑out homes, ask a professional whether zoning or strategically located sensors could reduce hot and cold spots and save energy.

How to Spot These Problems in Your Own Home

Because these issues are “invisible,” it helps to watch for patterns instead of waiting for an obvious breakdown.

Warning signs include:

One or two rooms that are always uncomfortable compared to the rest of the house, regardless of thermostat setting.

Energy bills that seem high for the size of the home and the age of the equipment.

Persistent dust, musty smells, or allergy symptoms even when filters are changed regularly.

If your home was built before 2000 and you notice any of these, a thorough inspection focused on ductwork, airflow, and controls can uncover problems that simple “tune‑ups” miss. Addressing these five invisible HVAC problems can extend equipment life, lower bills, and make your home far more comfortable season after season.